[RE-EDITED] Again as usual.

OK, it's just about that time of year again, so I decided to BUMP this old topic back up to the top again, as I have done every year since this was originally posted back on Monday November 23,2009 at 10:56 PM in the evening, Mountain Standard time.

Here in the USA, every year, on the last Thursday of November, we celebrate Thanksgiving Day, and so, this year, Thanksgiving Day falls on Thursday of November 24, 2011.

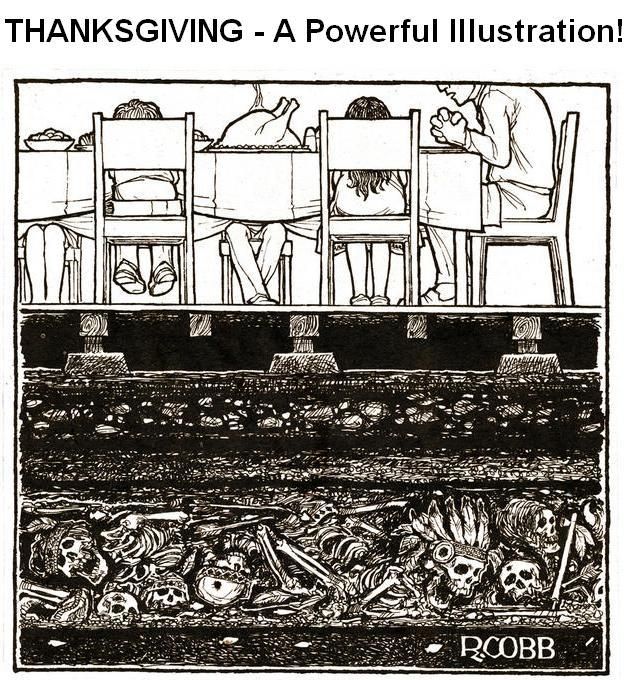

Oh, and here's a nice cheerful little reminder of what TURKEY DAY, or what I call, PIG OUT AND CHOW DOWN DAY, is really all about!

On this day, we "give thanks to God" for all we have, and we have a big feast, usually turkey with stuffing, yams or sweet potatoes, cranberries or cranberry sauce, and some pies, usually apple pies and pumpkin pies. I'm partial to pecan pies myself.

Well, I have a hard fast rule in my home.

When I have any guests over for them big feast, my hard fast rule is . . . . .

. . . ABSOLUTELY NO PRAYING AND GIVING THANKS TO GOD, BECAUSE GOD HAD ABSOLUTELY NOTHING TO DO WITH IT!

No, instead, I thank the farmers who grew the crops and raised the animals. I thank the truck drivers and the drivers of the trains who shipped the goods to the cities and to the markets. I thank the construction workers who built the roads and bridges and the railroad tracks that made the transportation of goods possible, and I thank the builders of the supermarkets, the electricians who installed the lights and the refrigeration units to preserve the food in the super markets.

God had nothing to do with it.

Yeah, we all know the story, written in so many school history books, about how the Pilgrims left England to "escape persecution" and how they came over on the Mayflower and settled at Plymouth Rock where they would have the freedom to practice their religion free from any persecution.

In their first year in The New World, about half of the Pilgrims died off from hunger during their first Winter, and then, when Spring came, a native tribe taught the Pilgrims how to plant crops, how to hunt and fish so that there would be plenty to eat when the first harvest came in.

And so, they had a big feast. The natives were invited to join in the feast, hence, the very first Thanksgiving celebration.

Well, to me, Thanksgiving is no longer a religious holiday, but just another holiday that I prefer to call TURKEY DAY. To me, it's just another excuse for me to make a glutton of myself. All I care about is the food.

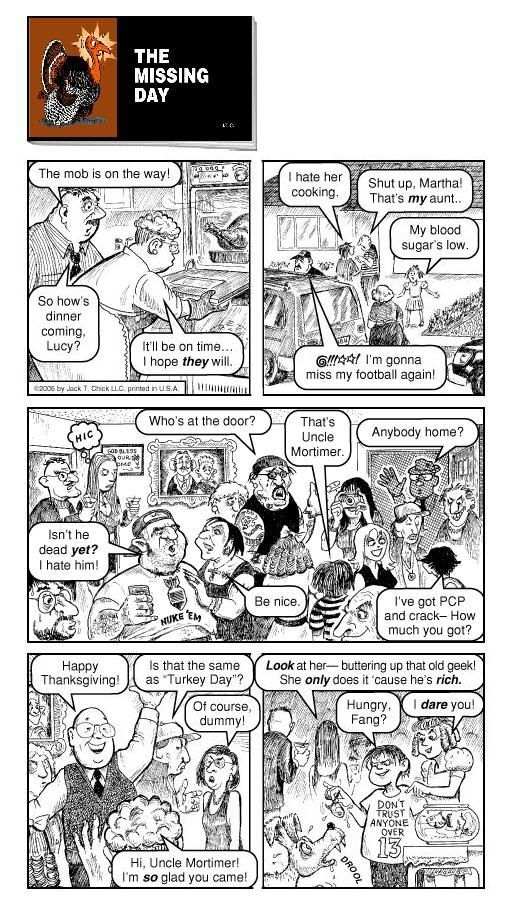

OK, here is a cartoon from a Fundamentalist Christian web site by J T Chick depicting a Thanksgiving story.

OK! OK! ENOUGH OF THIS BULLSHIT! SO LET'S JUST CUT THE CRAP RIGHT HERE AND NOW!!!

If you all wish to read the rest of this cartoon, just go to:

https://www.chick.com/reading/tracts/1025/1025_01.asp

In the meantime . . . . . . .

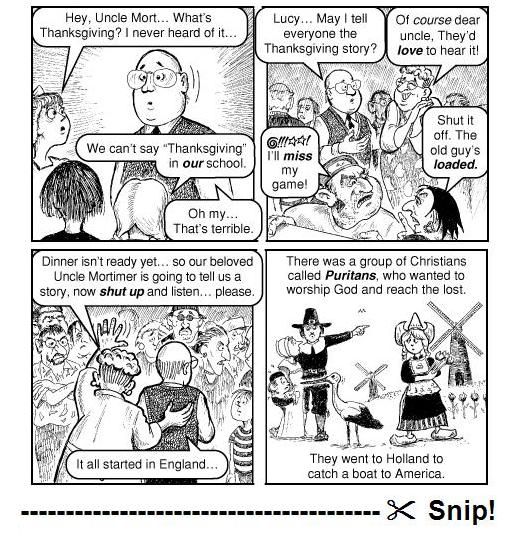

Just who were these Puritans anyway???

Well OK boys and girls, just sit back and relax as your Uncle Fat Man tells you the truth behind the stories of the Puritans.

In all the school history books, we are told that they suffered persecution in England because of their religious beliefs, so they went to Holland, and booked passage on the Mayflower to "The New World" across the Atlantic Ocean and settled on the shores of what is now the USA, and named their new settlement Plymouth Rock.

They came here for the sake of "religious freedom" or so we are told in all the school history books.

But here are some rather unpleasant truths about the Puritans.

When the colonies were more fully established, the Puritans embarked on their own campaign of persecution against all other religions within the colonies. The Puritans were especially hard on the gentle Quakers, and came down really heavy on them.

The Quakers were rather conservative, and they were kind of strict in some ways, but they were a gentle people, and although strict on their own, they were far more tolerant of other religions and other cultures than were the Puritans.

The Quakers wore dark colored clothing, mostly black, but they more were tolerant toward how people outside their religion were dressed. Also, another thing that is cool about the Quakers was that a couple of centuries later during the Civil War, the Quakers organized what was known as The Underground Railway that secretly helped many black slaves to escape from the south and toward the north for their freedom. The Quakers were always at the forefront when it came to standing up for human rights, so, although kind of strict, they were also kind of cool. I wouldn't care to be a Quaker myself, but I do admire them.

Anyway . . . . .

Here is some more history from a web site at:

http://thehistoricpresent.wordpress.com ... d-quakers/

Oh! It gets even better!!!Why the Puritans persecuted Quakers

Posted on July 2, 2008

It seems simple enough: the Puritans believed Quakers were heretics. In fact, anyone who was not an Anglican was a heretic, including Catholics, Lutherans, Anabaptists, Antinomians, Quakers, Rantersâ?¦ in short, anyone who was not Anglican.

Heretics were seen as blasphemers who put barriers in the way of salvation; they were also considered traitors to their country because they did not belong to the official state religion. This was true throughout Europe in the century following the Protestant Reformation: whatever religion the king chose became the official state religion of his country, and all other religions or sects were made illegal. In fact, the Puritans had left England because they had been considered heretics there, and had been persecuted by the government.

So when Quakers showed up in Boston in the 1650s, itâ??s no surprise they were persecuted. Puritan Congregationalism was the officialâ??and onlyâ??religion of New England. But it wasnâ??t just about their religion. The persecution of Quakers was also part of the Puritansâ?? determination to rule themselves, independent of England.

The Puritans who had remained in England during the Great Migration to America of the 1630s drifted apart from their New England brethren. They were more inclined to allow toleration of other professions of Christian faith. The impossibility of reforming, or purifying, the Anglican Church in England was slowly rejected in favor of the much more doable task of simply confirming England as a Protestant nation by allowing any and all Protestants to worship relatively freely. The English Puritans also supported Presbyterianism, a system in which the state governs the church and appoints a hierarchy to oversee all churches.

To the New England Puritans, both toleration and Presbyterianism were unacceptable. They had spent painstaking years establishing a system of church government called the New England Way that was based on the independence and power of the individual congregation. The state in Massachusetts did not appoint clergy, nor was there one over-arching body that regulated churches. Each church was a sovereign unit. And only one church was tolerated in Massachusetts: the Puritan, or Congregational church.

Worried that the English government would try to force its new rules of toleration and Presbyterianism on them, the Puritans of Massachusetts made preparations to fight for their independence. They elected their own governor and General Court (a combined legislature and judiciary). They built many forts to protect their harbor and drilled their militia men regularly. And they continued to persecute Quakers, who, determined to bring their version of the Gospel to New England, continued to trespass into Boston despite the harsh and often cruel punishments they knew they would receive.

The Quakers had no one to turn to for help until 1660, when the monarchy in England was restored, and Charles II came to the throne. One of his first acts as king was to send a letter to the governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony (the most powerful New England colony) ordering the persecutions of Quakers to stop. According to the â??Kingâ??s Missive,â? any Quaker accused of breaking the law in Massachusetts should be sent unharmed to England for trial.

Charles II issued his order for two reasons. First, it was a not too-well-kept secret that he was a Catholic sympathizer, and Quakers and Catholics were about the only groups who found absolutely no acceptance in England. If Charles could win tolerance for Quakers, perhaps he could win eventual tolerance for Catholics. Second, he cast a dark eye on Massachusettsâ?? independence. Disgruntled ex-colonists who left New England to return home told Charles the Puritans were rebels. It didnâ??t help that two of the judges who had condemned his father, Charles I, to death had fled to New Haven and received a heroâ??s welcome there.

The new king put Massachusetts in a bind: either they let the Quakers go free, or they give up the authority of their locally elected General Court. If they gave up the authority to prosecute Quakers, what other bit of their independence would they have to give up next? It was a slippery slope leading to direct English rule. Massachusetts made its choice. Slowly the persecution of Quakers came to an end.

This battle between king and colonies would go on until 1691, when Massachusettsâ?? charter was revoked and the powerful colony came at last under direct rule from England. By that time, toleration was the rule even in New England, and Quakers were no longer a dangerous and radical sect but commonplace members of society. But resentment of English rule did not die out amongst New Englanders; less than 100 years later, the descendants of the Puritans would buck off English rule in America for good.

This is from another web site at:

http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/project ... /salem.htm

This is what the Puritans had contributed to the Early American Colonies.Salem Witchcraft Trials 1692

"Examination of a Witch" in Salem.

An Account of Events in Salem

by Douglas O. Linder

From June through September of 1692, nineteen men and women, all having been convicted of witchcraft, were carted to Gallows Hill, a barren slope near Salem Village, for hanging. Another man of over eighty years was pressed to death under heavy stones for refusing to submit to a trial on witchcraft charges. Hundreds of others faced accusations of witchcraft; dozens languished in jail for months without trials until the hysteria that swept through Puritan Massachusetts subsided.

The Witchcraft Trials in Salem: A Commentary

by Douglas Linder

O Christian Martyr Who for Truth could die

When all about thee Owned the hideous lie!

The world, redeemed from superstition's sway,

Is breathing freer for thy sake today.

-Words written by John Greenleaf Whittier and inscribed on a monument marking

the grave of Rebecca Nurse, one of the condemned "witches" of Salem.

From June through September of 1692, nineteen men and women, all having been convicted of witchcraft, were carted to Gallows Hill, a barren slope near Salem Village, for hanging. Another man of over eighty years was pressed to death under heavy stones for refusing to submit to a trial on witchcraft charges. Hundreds of others faced accusations of witchcraft. Dozens languished in jail for months without trials. Then, almost as soon as it had begun, the hysteria that swept through Puritan Massachusetts ended.

Why did this travesty of justice occur? Why did it occur in Salem? Nothing about this tragedy was inevitable. Only an unfortunate combination of an ongoing frontier war, economic conditions, congregational strife, teenage boredom, and personal jealousies can account for the spiraling accusations, trials, and executions that occurred in the spring and summer of 1692.

In 1688, John Putnam, one of the most influential elders of Salem Village, invited Samuel Parris, formerly a marginally successful planter and merchant in Barbados, to preach in the Village church. A year later, after negotiations over salary, inflation adjustments, and free firewood, Parris accepted the job as Village minister. He moved to Salem Village with his wife Elizabeth, his six-year-old daughter Betty, niece Abagail Williams, and his Indian slave Tituba, acquired by Parris in Barbados.

The Salem that became the new home of Parris was in the midst of change: a mercantile elite was beginning to develop, prominent people were becoming less willing to assume positions as town leaders, two clans (the Putnams and the Porters) were competing for control of the village and its pulpit, and a debate was raging over how independent Salem Village, tied more to the interior agricultural regions, should be from Salem, a center of sea trade.

Sometime during February of the exceptionally cold winter of 1692, young Betty Parris became strangely ill. She dashed about, dove under furniture, contorted in pain, and complained of fever. The cause of her symptoms may have been some combination of stress, asthma, guilt, boredom, child abuse, epilepsy, and delusional psychosis. The symptoms also could have been caused, as Linda Caporael argued in a 1976 article in Science magazine, by a disease called "convulsive ergotism" brought on by ingesting rye--eaten as a cereal and as a common ingredient of bread--infected with ergot. (Ergot is caused by a fungus which invades developing kernels of rye grain, especially under warm and damp conditions such as existed at the time of the previous rye harvest in Salem. Convulsive ergotism causes violent fits, a crawling sensation on the skin, vomiting, choking, and--most interestingly--hallucinations. The hallucinogenic drug LSD is a derivative of ergot.) Many of the symptoms or convulsive ergotism seem to match those attributed to Betty Parris, but there is no way of knowing with any certainty if she in fact suffered from the disease--and the theory would not explain the afflictions suffered by others in Salem later in the year.

At the time, however, there was another theory to explain the girls' symptoms. Cotton Mather had recently published a popular book, "Memorable Providences," describing the suspected witchcraft of an Irish washerwoman in Boston, and Betty's behavior in some ways mirrored that of the afflicted person described in Mather's widely read and discussed book. It was easy to believe in 1692 in Salem, with an Indian war raging less than seventy miles away (and many refugees from the war in the area) that the devil was close at hand. Sudden and violent death occupied minds.

Talk of witchcraft increased when other playmates of Betty, including eleven-year-old Ann Putnam, seventeen-year-old Mercy Lewis, and Mary Walcott, began to exhibit similar unusual behavior. When his own nostrums failed to effect a cure, William Griggs, a doctor called to examine the girls, suggested that the girls' problems might have a supernatural origin. The widespread belief that witches targeted children made the doctor's diagnosis seem increasing likely.

A neighbor, Mary Sibley, proposed a form of counter magic. She told Tituba to bake a rye cake with the urine of the afflicted victim and feed the cake to a dog. (Dogs were believed to be used by witches as agents to carry out their devilish commands.) By this time, suspicion had already begun to focus on Tituba, who had been known to tell the girls tales of omens, voodoo, and witchcraft from her native folklore. Her participation in the urine cake episode made her an even more obvious scapegoat for the inexplicable.

Meanwhile, the number of girls afflicted continued to grow, rising to seven with the addition of Ann Putnam, Elizabeth Hubbard, Susannah Sheldon, and Mary Warren. According to historian Peter Hoffer, the girls "turned themselves from a circle of friends into a gang of juvenile delinquents." (Many people of the period complained that young people lacked the piety and sense of purpose of the founders' generation.) The girls contorted into grotesque poses, fell down into frozen postures, and complained of biting and pinching sensations. In a village where everyone believed that the devil was real, close at hand, and acted in the real world, the suspected affliction of the girls became an obsession.

Sometime after February 25, when Tituba baked the witch cake, and February 29, when arrest warrants were issued against Tituba and two other women, Betty Parris and Abigail Williams named their afflictors and the witchhunt began. The consistency of the two girls' accusations suggests strongly that the girls worked out their stories together. Soon Ann Putnam and Mercy Lewis were also reporting seeing "witches flying through the winter mist." The prominent Putnam family supported the girls' accusations, putting considerable impetus behind the prosecutions.

The first three to be accused of witchcraft were Tituba, Sarah Good, and Sarah Osborn. Tituba was an obvious choice. Good was a beggar and social misfit who lived wherever someone would house her, and Osborn was old, quarrelsome, and had not attended church for over a year. The Putnams brought their complaint against the three women to county magistrates Jonathan Corwin and John Hathorne, who scheduled examinations for the suspected witches for March 1, 1692 in Ingersoll's tavern. When hundreds showed up, the examinations were moved to the meeting house. At the examinations, the girls described attacks by the specters of the three women, and fell into their by then perfected pattern of contortions when in the presence of one of the suspects. Other villagers came forward to offer stories of cheese and butter mysteriously gone bad or animals born with deformities after visits by one of the suspects. The magistrates, in the common practice of the time, asked the same questions of each suspect over and over: Were they witches? Had they seen Satan? How, if they are were not witches, did they explain the contortions seemingly caused by their presence? The style and form of the questions indicates that the magistrates thought the women guilty.

The matter might have ended with admonishments were it not for Tituba. After first adamantly denying any guilt, afraid perhaps of being made a scapegoat, Tituba claimed that she was approached by a tall man from Boston--obviously Satan--who sometimes appeared as a dog or a hog and who asked her to sign in his book and to do his work. Yes, Tituba declared, she was a witch, and moreover she and four other witches, including Good and Osborn, had flown through the air on their poles. She had tried to run to Reverend Parris for counsel, she said, but the devil had blocked her path. Tituba's confession succeeded in transforming her from a possible scapegoat to a central figure in the expanding prosecutions. Her confession also served to silence most skeptics, and Parris and other local ministers began witch hunting with zeal.

Soon, according to their own reports, the spectral forms of other women began attacking the afflicted girls. Martha Corey, Rebecca Nurse, Sarah Cloyce, and Mary Easty were accused of witchcraft. During a March 20 church service, Ann Putnam suddenly shouted, "Look where Goodwife Cloyce sits on the beam suckling her yellow bird between her fingers!" Soon Ann's mother, Ann Putnam, Sr., would join the accusers. Dorcas Good, four-year-old daughter of Sarah Good, became the first child to be accused of witchcraft when three of the girls complained that they were bitten by the specter of Dorcas. (The four-year-old was arrested, kept in jail for eight months, watched her mother get carried off to the gallows, and would "cry her heart out, and go insane.") The girls accusations and their ever more polished performances, including the new act of being struck dumb, played to large and believing audiences.

Stuck in jail with the damning testimony of the afflicted girls widely accepted, suspects began to see confession as a way to avoid the gallows. Deliverance Hobbs became the second witch to confess, admitting to pinching three of the girls at the Devil's command and flying on a pole to attend a witches' Sabbath in an open field. Jails approached capacity and the colony "teetered on the brink of chaos" when Governor Phips returned from England. Fast action, he decided, was required.

Phips created a new court, the "court of oyer and terminer," to hear the witchcraft cases. Five judges, including three close friends of Cotton Mather, were appointed to the court. Chief Justice, and most influential member of the court, was a gung-ho witch hunter named William Stoughton. Mather urged Stoughton and the other judges to credit confessions and admit "spectral evidence" (testimony by afflicted persons that they had been visited by a suspect's specter). Ministers were looked to for guidance by the judges, who were generally without legal training, on matters pertaining to witchcraft. Mather's advice was heeded. The judges also decided to allow the so-called "touching test" (defendants were asked to touch afflicted persons to see if their touch, as was generally assumed of the touch of witches, would stop their contortions) and examination of the bodies of accused for evidence of "witches' marks" (moles or the like upon which a witch's familiar might suck). Evidence that would be excluded from modern courtrooms-- hearsay, gossip, stories, unsupported assertions, surmises -- was also generally admitted. Many protections that modern defendants take for granted were lacking in Salem: accused witches had no legal counsel, could not have witnesses testify under oath on their behalf, and had no formal avenues of appeal. Defendants could, however, speak for themselves, produce evidence, and cross-examine their accusers. The degree to which defendants in Salem were able to take advantage of their modest protections varied considerably, depending on their own acuteness and their influence in the community.

The first accused witch to be brought to trial was Bridget Bishop. Almost sixty years old, owner of a tavern where patrons could drink cider ale and play shuffleboard (even on the Sabbath), critical of her neighbors, and reluctant to pay her her bills, Bishop was a likely candidate for an accusation of witchcraft. The fact that Thomas Newton, special prosecutor, selected Bishop for his first prosecution suggests that he believed the stronger case could be made against her than any of the other suspect witches. At Bishop's trial on June 2, 1692, a field hand testified that he saw Bishop's image stealing eggs and then saw her transform herself into a cat. Deliverance Hobbs, by then probably insane, and Mary Warren, both confessed witches, testified that Bishop was one of them. A villager named Samuel Grey told the court that Bishop visited his bed at night and tormented him. A jury of matrons assigned to examine Bishop's body reported that they found an "excrescence of flesh." Several of the afflicted girls testified that Bishop's specter afflicted them. Numerous other villagers described why they thought Bishop was responsible for various bits of bad luck that had befallen them. There was even testimony that while being transported under guard past the Salem meeting house, she looked at the building and caused a part of it to fall to the ground. Bishop's jury returned a verdict of guilty. One of the judges, Nathaniel Saltonstall, aghast at the conduct of the trial, resigned from the court. Chief Justice Stoughton signed Bishop's death warrant, and on June 10, 1692, Bishop was carted to Gallows Hill and hanged.

As the summer of 1692 warmed, the pace of trials picked up. Not all defendants were as disreputable as Bridget Bishop. Rebecca Nurse was a pious, respected woman whose specter, according to Ann Putnam, Jr. and Abagail Williams, attacked them in mid March of 1692. Ann Putnam, Sr. added her complaint that Nurse demanded that she sign the Devil's book, then pinched her. Nurse was one of three Towne sisters, all identified as witches, who were members of a Topsfield family that had a long-standing quarrel with the Putnam family. Apart from the evidence of Putnam family members, the major piece of evidence against Nurse appeared to be testimony indicating that soon after Nurse lectured Benjamin Houlton for allowing his pig to root in her garden, Houlton died. The Nurse jury returned a verdict of not guilty, much to the displeasure of Chief Justice Stoughton, who told the jury to go back and consider again a statement of Nurse's that might be considered an admission of guilt (but more likely an indication of confusion about the question, as Nurse was old and nearly deaf). The jury reconvened, this time coming back with a verdict of guilty. On July 19, 1692, Nurse rode with four other convicted witches to Gallows Hill.

Persons who scoffed at accusations of witchcraft risked becoming targets of accusations themselves. One man who was openly critical of the trials paid for his skepticism with his life. John Proctor, a central figure in Arthur Miller's fictionalized account of the Salem witch hunt, The Crucible, was an opinionated tavern owner who openly denounced the witch hunt. Testifying against Proctor were Ann Putnam, Abagail Williams, Indian John (a slave of Samuel Parris who worked in a competing tavern), and eighteen-year-old Elizabeth Booth, who testified that ghosts had come to her and accused Proctor of serial murder. Proctor fought back, accusing confessed witches of lying, complaining of torture, and demanding that his trial be moved to Boston. The efforts proved futile. Proctor was hanged. His wife Elizabeth, who was also convicted of witchcraft, was spared execution because of her pregnancy (reprieved "for the belly").

No execution caused more unease in Salem than that of the village's ex-minister, George Burroughs. Burroughs, who was living in Maine in 1692, was identified by several of his accusers as the ringleader of the witches. Ann Putnam claimed that Burroughs bewitched soldiers during a failed military campaign against Wabanakis in 1688-89, the first of a string of military disasters that could be blamed on an Indian-Devil alliance. In her interesting book, In the Devil's Snare, historian Mary Beth Norton argues that the large number of accusations against Burroughs, and his linkage to the frontier war, is the key to understanding the Salem trials. Norton contends that the enthusiasm of the Salem court in prosecuting the witchcraft cases owed in no small measure to the judges' desire to shift the "blame for their own inadequate defense of the frontier." Many of the judges, Norton points out, played lead roles in a war effort that had been markedly unsuccessful.

Among the thirty accusers of Burroughs was nineteen-year-old Mercy Lewis, a refugee of the frontier wars. Lewis, the most imaginative and forceful of the young accusers, offered unusually vivid testimony against Burroughs. Lewis told the court that Burroughs flew her to the top of a mountain and, pointing toward the surrounding land, promised her all the kingdoms if only she would sign in his book (a story very similar to that found in Matthew 4:8). Lewis said, "I would not write if he had throwed me down on one hundred pitchforks." At an execution, a defendant in the Puritan colonies was expected to confess, and thus to save his soul. When Burroughs on Gallows Hill continued to insist on his innocence and then recited the Lord's Prayer perfectly (something witches were thought incapable of doing), the crowd reportedly was "greatly moved." The agitation of the crowd caused Cotton Mather to intervene and remind the crowd that Burroughs had had his day in court and lost.

One victim of the Salem witch hunt was not hanged, but rather pressed under heavy stones until his death. Such was the fate of octogenarian Giles Corey who, after spending five months in chains in a Salem jail with his also accused wife, had nothing but contempt for the proceedings. Seeing the futility of a trial and hoping that by avoiding a conviction, his farm, that would otherwise go the state, might go to his two sons-in-law, Corey refused to stand for trial. The penalty for such a refusal was peine et fort, or pressing. Three days after Corey's death, on September 22, 1692, eight more convicted witches, including Giles' wife Martha, were hanged. They were the last victims of the witch hunt.

By early autumn of 1692, Salem's lust for blood was ebbing. Doubts were developing as to how so many respectable people could be guilty. Reverend John Hale said, "It cannot be imagined that in a place of so much knowledge, so many in so small compass of land should abominably leap into the Devil's lap at once." The educated elite of the colony began efforts to end the witch-hunting hysteria that had enveloped Salem. Increase Mather, the father of Cotton, published what has been called "America's first tract on evidence," a work entitled Cases of Conscience, which argued that it "were better that ten suspected witches should escape than one innocent person should be condemned." Increase Mather urged the court to exclude spectral evidence. Samuel Willard, a highly regarded Boston minister, circulated Some Miscellany Observations, which suggested that the Devil might create the specter of an innocent person. Mather's and Willard's works were given to Governor Phips. The writings most likely influenced the decision of Phips to order the court to exclude spectral evidence and touching tests and to require proof of guilt by clear and convincing evidence. With spectral evidence not admitted, twenty-eight of the last thirty-three witchcraft trials ended in acquittals. The three convicted witches were later pardoned. In May of 1693, Phips released from prison all remaining accused or convicted witches.

By the time the witch hunt ended, nineteen convicted witches were executed, at least four accused witches had died in prison, and one man, Giles Corey, had been pressed to death. About one to two hundred other persons were arrested and imprisoned on witchcraft charges. Two dogs were executed as suspected accomplices of witches.

Scholars have noted potentially telling differences between the accused and the accusers in Salem. Most of the accused lived to the south of, and were generally better off financially, than most of the accusers. In a number of cases, accusing families stood to gain property from the convictions of accused witches. Also, the accused and the accusers generally took opposite sides in a congregational schism that had split the Salem community before the outbreak of hysteria. While many of the accused witches supported former minister George Burroughs, the families that included the accusers had--for the most part--played leading roles in forcing Burroughs to leave Salem. The conclusion that many scholars draw from these patterns is that property disputes and congregational feuds played a major role in determining who lived, and who died, in 1692.

A period of atonement began in the colony following the release of the surviving accused witches. Samuel Sewall, one of the judges, issued a public confession of guilt and an apology. Several jurors came forward to say that they were "sadly deluded and mistaken" in their judgments. Reverend Samuel Parris conceded errors of judgment, but mostly shifted blame to others. Parris was replaced as minister of Salem village by Thomas Green, who devoted his career to putting his torn congregation back together. Governor Phips blamed the entire affair on William Stoughton. Stoughton, clearly more to blame than anyone for the tragic episode, refused to apologize or explain himself. He criticized Phips for interfering just when he was about to "clear the land" of witches. Stoughton became the next governor of Massachusetts.

The witches disappeared, but witch hunting in America did not. Each generation must learn the lessons of history or risk repeating its mistakes. Salem should warn us to think hard about how to best safeguard and improve our system of justice.

The Puritans who had come here to "escape religious persecution" in England, had inflicted their own brand of persecution on anybody who was not of their religion after the colonies were fully established.

Yes, the Puritans claim they were here for their "religious freedom" yet, they would not allow the same for anybody else in the colonies.

The Puritans who left England were the dregs of English society. They were simply ignorant and superstitious low-life scum!

Had they not been allowed the choice of getting on a boat to the New World, they would most likely had been deported to Botany Bay, a prison colony in Wales, that is . . . if it had existed at the time. But Botany Bay was not established until 1788, so these scums were allowed the option to get on a rinky-dink rat-infested boat to sail off to The New World, otherwise, if the Puritans had stayed in England, most likely, they would have been shot, or hanged, or ended up in prison since they were all such low-life scum-bags. So, they were lucky to book passage on the Mayflower to sail off to The New World.

Like, WWWHHHOOOOOOOOOOOOOPEEEEEEE!!!

Actually, the inmates in the prison colony at Botany Bay were a far better class of people than the low-life scums who settled at Plymouth Rock!

Also, during their first year after settling at Plymouth Rock, they were so stupid they could not survive without the help of a local Native American tribe who taught them how to hunt, and plant crops.

And years later, how did the Puritans thank these native tribes?!?

Yeah! We know!

But that's another story!

To me, Thanksgiving is NOT a religious holiday!

To me, it's only another secular holiday that I call Turkey Day, and I do celebrate it by having a great big turkey with stuffing, cranberry sauce, yams or sweet potatoes, and some pies for dessert.

That's because I'm a Fat Man who loves to eat, so to me, Turkey Day is just another excuse to pig-out and chow-down, and it no longer has any religious significance for me.

So, to everybody here who lives in the good ol' USA!

HAPPY TURKEY DAY!

I'm fat and sassy! I love to sing & dance & stomp my feet & really rock your world!

I'm fat and sassy! I love to sing & dance & stomp my feet & really rock your world!